|

|

Speaking of Charlton and DC, these two companies were able to survive the Code. Charlton

was a low-cost house, paying some of the worst page rates in the industry, and while DC paid as well or

better than anyone, their generally conservative publishing approach seldom ran afoul of the Code in its

early days. By 1956 they had actually started the Silver Age of Comics with Showcase #4.

Both companies were also helped by acquiring properties of houses that didn't survive, with DC taking on

the Quality characters and Charlton acquiring those of Fawcett (except for the Marvel Family),

Fox, and Fiction House.

|

|

|

|

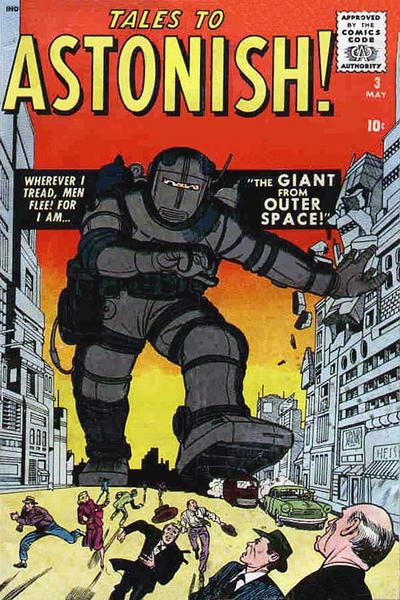

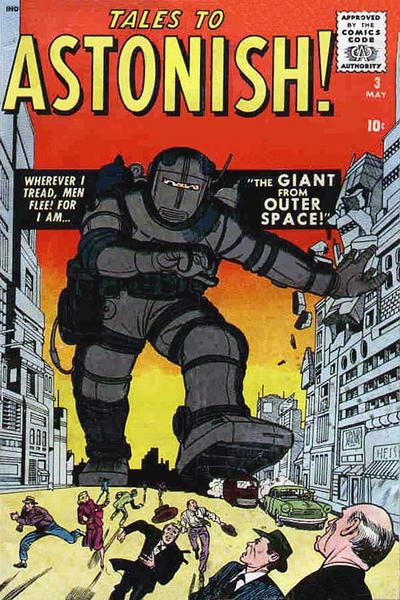

A not-too-scary monster fills the front cover of the Code-approved Tales to Astonish #3 (May 1959), art

by Jack Kirby and Christopher Rule.

|

Marvel (still known then as Atlas) was another story. Comics distributors had been on

shaky financial ground even before the Code, but just how shaky was revealed only after publisher

Martin Goodman closed down his Atlas distribution arm, which while it had been in operation had

enabled him to avoid some of the financial pressures that Gaines at EC could not. This was in 1957,

and Goodman figured that with sales low he'd be better off letting American News Company distribute

his books. But this turned out to be a rare miscalculation on Goodman's part as ANC itself soon fell despite

being the largest distributor (the reasons are complicated, but the Code certainly didn't help) and Goodman

suddenly had no way to get his books to the newsstand. Editor Stan Lee had to fire everyone,

and was left sitting alone in a small office.

Then there were the administrative costs of the Code. I've never read any claim that this hurt the industry,

but the Code office had a budget of something like $100,000 per year, and that money came right out of

the publishers' bottom lines. Probably most seriously, once ANC fell the remaining distributors

would not necessarily carry titles that sold below a certain minimum, and under these conditions the smaller

houses simply could not survive.

How much of all this was the Code's fault is debatable. Other factors, such as the new medium of television,

had clearly hurt the industry, but when profit margins are already small you can't afford any sudden hits,

and it's clear that the Code was injurious the content and therefore the sales of comic books. Goodman,

by the way, finally managed to save Atlas by the ingenious strategy of having DC distribute his books.

Yes, it's one of the little-known facts of comics history that there would have been no Marvel Age of Comics

had they not been distributed in their early years by rival publisher DC!

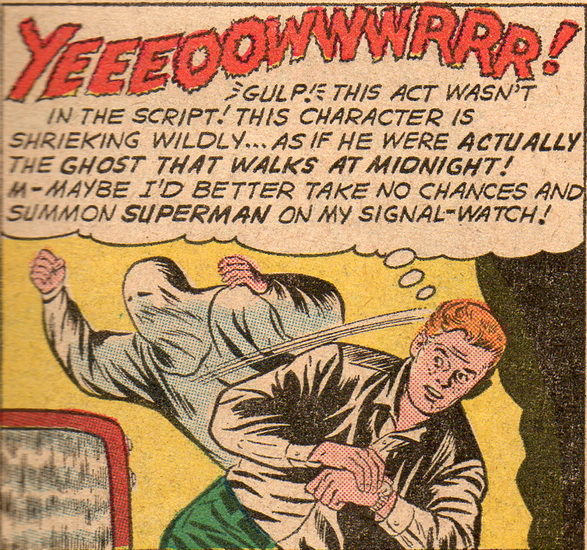

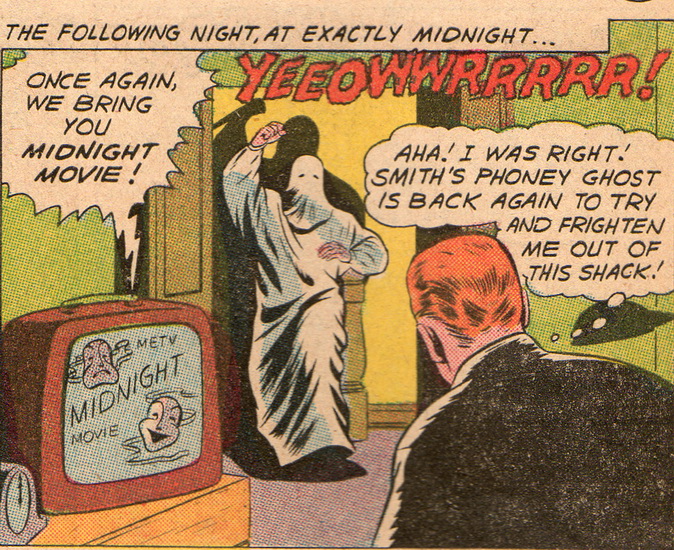

At left we see a post-Code issue of Tales to Astonish, which in a few years would be featuring

Ant-Man and The Hulk. But those characters hadn't been created yet, so at this time the

book featured rather tame menaces like the giant space man seen here. Notice that there's no blood, or

gore, or even anybody getting trampled.

|

|